4 min|Dr. Jam Caleda

Understanding The Mechanics of Pain

HealthPain can be a difficult thing to treat.

This mainly may be due to the fact that the way the body experiences pain is seldom attributable to one thing, particularly if it is chronic. The approach that many practitioners employ can be precise and accurate but can get lost in the minutia of mechanics and lose sight of the larger picture.

As a result, it is common to seek treatment and be prescribed a remedy for just one particular part of what is causing pain when a multidisciplinary approach might be more appropriate.

How Pain Works

Pain can be overwhelmingly paralyzing and encompass all of our attention; it can be insidious, slowly building momentum until we finally notice; it can manifest only when our attention is drawn to a previously unknown injury, or it can never occur at all even when we know it should. Essentially pain is whatever the person with pains says it is.

To understand this, we must understand that pain is a result of the physiologic context of the brain and the environment.Pain was initially defined by a tissue-based model, where it is a result of some injury in the surrounding tissue where the sensation is felt.

For example, if there is pain in the elbow, the reason must be that there is an injury to the elbow specifically. However, modern pain scientists such as Robert Melzack, Eyal Lederman, and Cary Brown are shifting away from this idea and expanding that pain, more so if it is chronic, results from the nervous system being alerted of a threat to the body.

Modern pain science describes it as coming from three pathways, nociceptive, peripheral, and central. These three categories are collectively described in a theory called the neuromatrix theory of pain.

This idea proposes that “pain is a multi-dimensional experience produced by characteristic “neurosignature” patterns of nerve impulses generated by a widely distributed neural network”. This means that there are pathways in the brain which when collectively activate and manifest the experience of pain.

Nociceptive pain is similar to the tissue-based model, where there is a physical stimulus to a region of the body, and that stimulus travels up a ‘nociceptive’ (pain) receptor to the brain where we interpret it as such. An example of this is when one stubs a toe.

Peripheral sensitization is more an explanation into the realm of chronic pain. This occurs when there is no longer a physical insult to the body, but because the nervous system has a memory it activates the same neurons that were alerted during the initial insult. What proceeds to occur is that the nervous system re-stimulates the sensation of pain to prevent us from recreating it. It does so by sensitizing the same pain neurons that were turned on during the initial injury.

As a result, even though the tissue that was initially damaged is healed, the neural tracts that run up to the brain are still firing. This is why old injuries can still be painful sometimes decades after it is healed.

Central sensitization is an explanation of pain that occurs for seemingly no reason at all as in some pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia and chronic regional pain syndrome. In people who do not suffer from central sensitization, the brain acts as a filtration system that filters stimuli that are coming from all parts of the body. This is necessary to be able to respond to change in our environment in an appropriate way.

In central sensitization this filtration system in the brain is dysfunctional, and we no longer are capable of differentiating painful from non-painful stimuli. So someone can interpret what is normally a mild or non-noxious signal as severely painful.

Takeaway

We are beginning to shift away from a strict tissue-based biomechanical model and learning more about the neuromatrix of the brain. This is important because it is giving us a better understanding of what and why things work. The resolution of change doesn’t come from only healing broken tissue but from impacting the nervous system and promoting changes from aberrant pathways.

There are numerous ways to support this change, and it includes manual therapy (adjustments, massage, Rolfing etc.), biochemical ‘inputs’ (medications, supplements, Regenerative Injections Therapies, neural therapy, etc.) and sometimes mindfulness practices.

In the end, providers don’t make those changes in neurology, the body does. We cannot force it to change but only learn to speak its language.

*Always consult with your health care practitioner before starting any treatment regime*

RESOURCES

1. Melzack, R. “Pain and the Neuromatrix in the Brain.” Journal of dental education 65.12 (2001): 1378–1382. Print.

2. Melzack R. Pain–an overview. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1999 Oct 1;43(9):880-4.

Related Articles

4 min|Dr. Alex Chan

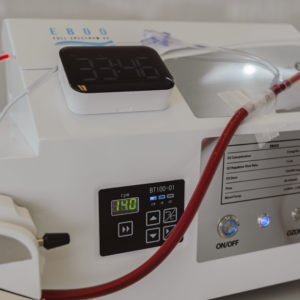

EBOO for Chronic Inflammation: A Natural Approach for Systemic Relief

Regenerative Medicine, EBOO Therapy

4 min|Dr. Alex Chan

EBOO Therapy for Autoimmune Conditions: Exploring the Potential Benefits

Autoimmune Disease, Regenerative Medicine, EBOO Therapy