6 min|Integrative

The Many Causes of Iron Deficiency

Wellness, Nutrition, Health, EducationIron deficiency is one of the most common nutritional deficiencies, particularly amongst women.

It is typically detected via measuring ferritin, the blood marker of iron storage. Ferritin will drop in the initial phase of iron deficiency, and may trigger symptoms, particularly as storage levels decrease. If iron storage is exhausted, iron deficiency anemia can occur, resulting in low hemoglobin, low hematocrit, low iron saturation, and increased total iron-binding capacity (TIBC).Iron deficiency can occur without anemia, and can create symptoms, whether or not anemia develops. A decrease in iron decreases oxygen availability throughout the body, as well as decreased myoglobin, the iron and oxygen binding protein in the muscles. Due to these widespread effects, the symptoms of iron deficiency can be vague, and range greatly in severity.

Possible Symptoms of Iron Deficiency

- Fatigue

- Tachycardia (rapid heart rate)

- Heart palpitations

- Lightheadedness, dizziness

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain, especially with exertion

- Reduced exercise intolerance

- Headache, especially with exertion

- Brittle nails

- Hair loss

- Pale or sallow skin

- Sore tongue

- Sores at the edges of the mouth

- Cold hands and feet

- Unusual cravings for non-nutritive items, such as ice, clay, or dirt

- ‘Whooshing’ in the ears

- Restless legs

- Heavy periods

- Hypothyroidism (due to a reduction in T4 to T3 conversion)

Conventional treatment for iron deficiency is typically iron supplementation. However, without investigating the root cause of iron deficiency, or iron-deficiency anemia, iron supplementation may not lead to improvements in iron levels, may exacerbate an underlying issue, or may fail to appropriately identify - and address - a significant health issue.

Possible Causes of Iron Deficiency

1. Lack of Dietary Intake of Iron

Iron deficiency can occur simply due to a lack of iron intake. Iron occurs in food in two forms - heme and nonheme iron. Heme iron occurs in animal proteins such as meat, poultry, and seafood, whereas non heme iron can be found in fortified cereals, dark chocolate, spinach, potatoes, nuts, and seeds. Heme iron occurs in high amounts in animal proteins, and is better absorbed by the body than non heme iron. For this reason, iron deficiency due to lack of dietary intake is of greater concern in people who limit their animal protein intake, such as vegetarians and vegans.Vegetarians are more likely to experience low ferritin and iron-deficiency anemia, especially premenopausal vegetarian women. (2) Interestingly, studies of both vegetarian men and women have shown low ferritin levels even in the presence of high non heme iron intake. (3,4) This indicates that high total iron intake may not be sufficient to establish healthy ferritin levels if occurring in the diet in mostly non heme form. This may be due to an issue of absorption, rather than total intake, which leads us to our next possible cause...

2. Lack of Absorption of Dietary Iron

At times, dietary intake - the food you ingest - may be sufficient, but the amount absorbed is insufficient to establish healthy iron levels within the body. It is not enough to ingest a nutrient, that nutrient must be able to be absorbed across the gut lining, into the bloodstream, to have an effect on our health. As discussed, absorption may not be optimal if we are ingesting mostly - or exclusively - non heme iron. Low stomach acid, also known as achlorhydria, can result in poor breakdown of foods rich in iron, leading to a reduction in iron absorption. Long-term usage of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) can lead to iron deficiency by way of malabsorption as a result of gastric acid inhibition. (5) These factors become particularly concerning for the elderly who already experience an age-related decline of stomach acid, and may consume a light, low-iron ‘toast and tea’ diet.Absorption can be greatly diminished in the presence of inflammatory diseases of the digestive tract, such as celiac disease. Iron is mostly absorbed in the duodenum, the portion of the small intestine that experiences the brunt of the inflammation and damage triggered by gluten in cases of celiac disease.

Certain gut infections, such as Helicobacter Pylori and parasitic worms, can interfere with absorption of dietary iron. (6, 7) Bacterial imbalances or overgrowth - such as in cases of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) - can interfere with absorption of iron due to bacterial usage of iron, as well as inflammatory blunting of the small intestine. (8) Gut microbiota generally appear to play a complex role in attenuating iron absorption. (9) Pathogens also appear to sequester iron to develop biofilms, complex accumulations of bacteria held together by polysaccharides. (10) Biofilms are an important survival mechanism for bacteria, but this adaptation, while protective for the bacteria, renders them difficult to treat and eradicate. Supplementation with iron in the presence of bacterial infections may provide the fuel source required for such biofilm formation.

3. Iron Loss & Increased Demand

Even in the presence of healthy iron intake, as well as adequate absorption, iron deficiency can occur due to significant iron loss or increased demand. Iron loss can occur due to a wound, such as with a traumatic injury or a gastrointestinal bleed, or due to heavy menstrual periods. During pregnancy, there is a much higher demand for iron, as it is required to support the growing fetus and placenta.Treatment Considerations

Simply increasing iron intake, via food or supplementation, may not address the root cause of iron deficiency. Additionally, depending on the root cause, increasing iron intake may not be a sufficient treatment to significantly impact ferritin levels. At worst, a mild or moderate increase in ferritin level as a result of iron supplementation may disguise a chronic condition, such as H. Pylori, Celiac disease, or a gastrointestinal bleed.Low ferritin, or blood indicators of iron-deficiency anemia, are signals; they are signs that you are not ingesting enough iron; not absorbing enough iron; are losing iron; have an increased demand for iron; or a combination of any of these factors. A skilled practitioner can work with you to evaluate what this signal is indicating and develop a plan that addresses the root cause.

REFERENCES

- https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/bc-guidelines/iron-deficiency#testing

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6367879/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14988640/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10201799/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jha2.96

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3710418/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5619638/

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/06/190607122406.htm

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1550413119305601

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01204/full

Related Articles

6 min|Dr. Alex Chan

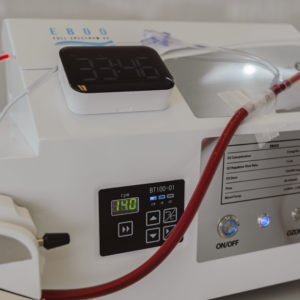

EBOO for Chronic Inflammation: A Natural Approach for Systemic Relief

Regenerative Medicine, EBOO Therapy

6 min|Dr. Alex Chan

EBOO Therapy for Autoimmune Conditions: Exploring the Potential Benefits

Autoimmune Disease, Regenerative Medicine, EBOO Therapy