5 min|Integrative

Digestion Begins in the Brain

Wellness, Nutrition, Education, Gut HealthWhen we think of the digestive system, we typically picture the long, winding path from the mouth down through the abdomen.

Depending on how much we’ve learned about our ‘gut’ over the years, we may also picture the individual organs, such as the stomach, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and intestines. But rarely do we picture the organ that governs over this entire system - the brain.The gut-brain connection is where it all begins. Our brain, and its interpretation of our surroundings, sends the necessary signal to the nervous system within the gut, also known as the enteric nervous system, that it is time to digest food. Alternatively, when stressed, our brain can signal to the enteric nervous system that it is time to shut down the digestive system and focus on more urgent responses. In turn, the enteric nervous system can send signals back to our brain, a pathway recently discovered to play a role in depression, (1) anxiety, (2) Parkinson’s disease, (3) and many other conditions. In this way, gastrointestinal distress can be the product of - or the cause - of mental distress.

The Threatened Gut

When our brain perceives a threat, the sympathetic nervous system is activated. Commonly known as the ‘fight, flight, or freeze’ response, the sympathetic nervous system puts us in a state of readiness to react to stress. Our pupils dilate, blood pressure rises, and glucose is released into the bloodstream to provide energy. In turn, the parasympathetic nervous system, also known as the ‘rest and digest’ response, is overridden, and digestive processes are halted; digestive enzymes and stomach acid are not released and fatty acid metabolism is impaired. Evolutionarily, this is an appropriate response - when we’re running for our lives, it is not the time to stop and have a snack.The Chronically Stressed Gut

However, nowadays the threat isn’t temporary. ‘Stress’ may not refer to a temporary event, but a chronic state of deadlines, pandemic anxiety, financial concerns, and health woes. At its most insidious, stress can be as simple as distraction, the constant flipping back-and-forth between email and social media alerts, the task at hand, and noise pollution.This kind of stress chronically activates the sympathetic nervous system response, overpowering the digestion-favoring parasympathetic system. This equates to an unequipped digestive tract; if food is consumed in this state, our digestive system has not released the juices necessary for digestion and absorption. Distraction alone can greatly interfere with the functioning of the digestive system; in a study of participants distracted by dissimilar audio tracks playing in each ear, a significant reduction in nutrient absorption was recorded. (4)

Additionally, chronic stress increases intestinal permeability, also known as ‘leaky gut’; (5) increases pro-inflammatory cytokine release; (6) and can shift the gut microbiome towards pathogenic overgrowth. (7) Metabolically, chronic stress can lower fat oxidation, decrease caloric expenditure, and increase insulin release, all factors which can equate to weight gain, particularly when they occur day after day. (8)

Over time, a chronically stressed brain leads to a chronically stressed gut, and can predispose us to weight gain, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), autoimmune diseases, and many other conditions, through complex pathways of inflammation, increased intestinal permeability, dysbiosis, and malabsorption.

Harness the Mind to Influence Your Gut

If the gut-brain connection can be hijacked by stress, it can in turn be harnessed by mindfulness, particularly by focusing on the cephalic phase of digestion. Cephalic literally means ‘head’, and refers to the first phase of digestion that actually begins before food even enters our stomach. This phase is triggered by the sight, smell, anticipation of a meal, and the taste of food, and is mediated by the vagus nerve and parasympathetic nervous fibers; memory, mood, association, and pleasure also all play a role. How our brain is interpreting the meal, and associated sensory information, influences the release of digestive juices and readiness of our digestive system. This phase of digestion is estimated to account for 30-50% of our stomach acid release and 25% of our pancreatic enzyme release. (9)Although we may not be able to eliminate all the stress in our lives, we can create dedicated mealtime rituals to encourage a healthy cephalic phase of digestion, the first step required for digestion and absorption:

- Devote Time to Preparation: The cephalic phase relies on all of your senses. Invoke them by taking the time to see, smell, and anticipate what you are about to eat.

- Eliminate Distractions: When you’re eating, only eat - this means sitting down, putting away your work, and turning off screens, notifications, and any other possible interruptions.

- Invite your Parasympathetic Nervous System: Your parasympathetic nervous system - the ‘rest-and-digest’ response - is required for healthy digestion. Engage it by activating your senses, eliminating distractions (stressors), and completing deep belly breaths prior to eating. Inhale deep enough that your belly rises, before exhaling; complete 4-6 times.

- Chew, then Chew a Bit More: Mastication - aka chewing - is the first step of digestion. The more you chew, the more the surface area of your food is increased, enabling efficient breakdown by digestive enzymes.

- Take Your Time: The entire experience of mealtime plays a role in digestion and absorption of nutrients, and is not an experience to be rushed. Put your utensil down between bites, enjoy your meal, and become present to how full you feel.

Are you looking for support with nutrition and gut imbalance? Click here to book a consultation with an Integrative Naturopathic Doctor.

REFERENCES

1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7213601/2. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0166223613000088

3. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2019.00574/full

4. https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/0016-5085(87)90319-2/pdf

5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24153250/

6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28245757/

7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12412628/

8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4289126/

9. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/cephalic-phase

Related Articles

5 min|Dr. Alex Chan

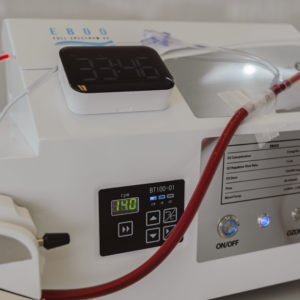

EBOO for Chronic Inflammation: A Natural Approach for Systemic Relief

Regenerative Medicine, EBOO Therapy

5 min|Dr. Alex Chan

EBOO Therapy for Autoimmune Conditions: Exploring the Potential Benefits

Autoimmune Disease, Regenerative Medicine, EBOO Therapy